In many countries of the world, while standing in front of an average supermarket shelf, the conscious consumer could be overwhelmed by the promise of a better world. There is an impressive assortment of labels claiming a product to be fair, ethical, sustainable, or at the least, good for the farmer, for the fishes or for reducing the loss of tropical forests.

In the Netherlands, the proliferation of these labels recently prompted an independent investigation to compile a list of the 10 “most reliable labels” out of more than 60 labels reviewed. Remarkably, the most prominent labels came out in the top 10 in the final list. Apparently, the market is functioning well and the best labels are also the dominant ones. Quality proves itself once again. Or is the reality of labels and certification more complex?

From the Max Havelaar to the Fair Trade label

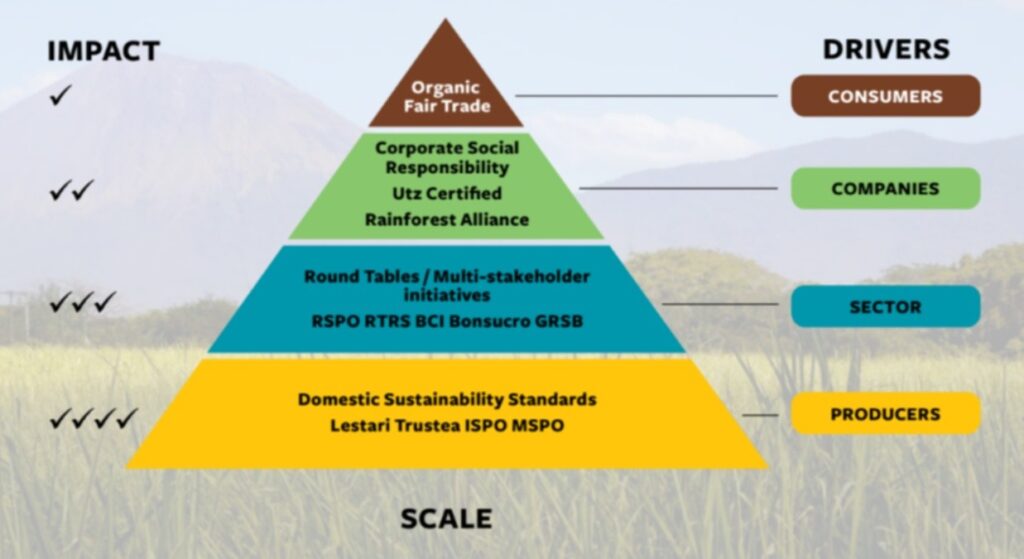

Sustainability labels are known as a form of ethical branding which gained popularity in the last quarter of the 20th century. Consumer labels for organic and fair trade products offered consumer support along with marketing potential for the first generation of ethical brands. Solidaridad initiated fair trade labeling by introducing the Max Havelaar label for coffee in the Dutch market in 1988 and for bananas in 1997 and expanded the concept to other European markets.

At the time, Solidaridad thought carefully about principles for effective branding and chose the name Max Havelaar for the new label. We rejected the name “fair trade” because we wanted to avoid a reluctance from the dominant market players for accepting the newly developed label. We felt that by calling the label fair trade, an implicit accusation was being made that all regular trade is intrinsically unfair.

We were also uncertain if the new label could fully justify the claim of being fair. Max Havelaar – an example of world renowned literature telling the story of coffee production in Indonesia under Dutch colonial rule with a clear ethical statement against colonial exploitation – was seen as a good alternative for the name fair trade and represented many of the economic and sustainability principles we were striving for. Solidaridad wanted to link the introduction of the new label with Max Havelaar’s brave history of the struggle for justice without overpromising what kind of change the label could bring.

After successfully introducing the label in the Netherlands, the Max Havelaar label was used for many years in Switzerland, Denmark, Belgium and France. With the growing dominance of Anglo-Saxon culture, the English language and the acceptance of modern marketing research, rebranding the Max Havelaar label as a “fair trade” label became inevitable.

In my view, the fair trade movement took a significant yet subtle risk with this choice. The adjective “fair” is not easily justified and runs the risk of overpromising in a world rife with persistent unfairness.

Utz simply means good

Along with introducing fair trade labeling, the second important role Solidaridad played in the history of certification was initiating an ambitious corporate social responsibility (CSR) label for the mainstream market. In 2001, Solidaridad persuaded Ahold Coffee Company to transform the Utz Kapeh company code for its sustainable coffee into a generally accessible and improved CSR code for a broader range of products.

From that transition, the Utz code was born and is now one of the largest certification programmes in the world. Utz means “good” in one of the Maya languages. Good is the first step from better to best. Solidaridad felt comfortable with this modest Utz positioning. And history is on our side. Utz certification turned out to be just the first step on a long journey to sustainability.

Rainforest Alliance and what about the rainforest?

Another prominent CSR label is the Rainforest Alliance. Their branding runs the risk of a contradiction between the messaging and the reality on the ground.

It is difficult to defend that the Rainforest Alliance has significantly contributed to a reduction of deforestation. The label has certainly contributed to smart and sustainable agricultural practices and can be valued for that. But these important innovations at farm level came after deforestation already took place.

The main drivers of deforestation are not really negated by the requirements of the Rainforest Alliance label. Other organizations like Greenpeace and WWF initiated more effective measures to reduce deforestation. But in all honesty, national regulations and effective enforcement of the law are actually more important in reducing deforestation than certification approaches.

From this perspective, organizations involved in sustainable development become vulnerable when their branding is not in line with their core programming.

Sustainable or responsible?

The third generation of certification approaches revolves around commodity roundtable initiatives which offer broad stakeholder involvement for sector improvements. As an example for the palm oil sector, the Round Table for Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) chose to emphasize sustainable palm oil production as the requirement for certification. For soy, the members of the Round Table for Responsible Soy (RTRS) were no less ambitious but more modest by using the word responsible as a focus for the programme.

Solidaridad favours the more realistic wording found in the RTRS approach with the understanding that their programme emphasizes the responsibility stakeholders share for driving improvements together. Even when promoting a sense of responsibility, there is still a long way to go to realize sustainable soy production. The Bonsucro and Better Cotton initiatives also followed a similar path for choosing a realistic position by bringing responsibility to the forefront of their messaging.

On the path to true and lasting sustainability, good and better still leaves room for improvements.

Pyramid of Change

Balancing messaging and reality

As the sustainability agenda evolves, we are currently moving from dark to white with grey shades in between. Neglecting this complexity will not help us. Claiming more than achieved will not create cre

dibility and trust. Moreover, when we stop questioning the efficiency of our ethical claims, we lose an essential stimulus for self-criticism and tend to seek support in anecdotal, untested evidence.

We are at a time now when critical expressions in the media about certifications keep popping up. Producers are not asking for a “policeman” but for a “doctor”. CSOs recognize they can not certify farmers out of poverty. End consumer companies, traders and farmers could lose their trust in certification because they don’t see it as a reliable and cost-effective way to achieve real sustainability. They may even start looking for alternatives if the trend continues. Sharp observers already see this happening. What has started as a community of change stimulating debate and innovation could end up in a community of believers defending vested interests and old thinking.

Underdeliver

I always get a little bit uneasy with the marketing messages suggesting that an income of €1.85 per day for a tea picker in Rwanda is a fair income or a living wage. Even if certification leads to an increase of 30 cents, this is still an unworthy income. If a coffee farmer in Uganda has raised his net income from 450 dollars to 850 dollars a year after 12 years of certification while his coffee is promoted as ethical, I feel similarly uneasy.

Promoting hand-picked certified coffee as traditional or artisanal is another questionable practice, as handpicking is a recipe for poverty. In fact, cocoa farmers in Ivory Coast are being forced back under the poverty line after seemingly helpful investments in higher productivity led to lower prices for cocoa. The overall picture is that persistent problems remain and systemic change fails.

Overpromise

Initially, I was pleasantly surprised with a recent Iseal publication presenting attractive infographics reporting “direct contributions of certification” towards achieving sustainability goals. However, after taking a closer look, and assessing the information with well-informed people in my network, important nuances begin to arise. A lot of the presented achievements are not the result of certification, or at best, they are only indirect effects. Improvements are made because of investments by farmers or businesses, trainings offered by CSOs, support from local governments or improved regulations, not certification alone.

Often better access to finance, innovative technologies, diversification, local market development or the establishment of a local processing industry for agricultural produce provides more important contributions to robust agricultural structures than certification. From a professional point of view, a clearer distinction between attributions and contributions would have been helpful to get a better understanding of the unique significance of certification among the many other interventions taking place. Distributing “diplomas” does not give the right to claim all contributions to the “curriculum” as attributions of certification.

“We see the emergence of a claiming culture. Monitoring and evaluation is not primarily for learning, but in order to claim results and impact. For proving, not improving. But let’s be cautious. The real contribution to success comes from producers who are improving their practices, workers who are organizing themselves and miners struggling for legalization, as well as courageous women who are breaking through cultural barriers. They are the real actors for change.” – Solidaridad Network Annual Report 2013

Beyond certification

Confusing attributions and contributions contaminate the public debate about the future of certification. In my review of developments over the past decades, I found an old and yellowing discussion paper from 1986 in my personal files which forcefully advocated for the introduction of “certification as a new concept for development cooperation”, which was a relatively new concept at that time. I easily recalled my argumentation as the initial drivers for taking this new step.

The added value of certification that Solidaridad was looking for was the development of consumer demand for sustainable products based on a distinction between sustainable and unsustainable products, and create a premium for sustainable products. All at the lowest possible cost to avoid a competitive disadvantage. A code of conduct and third party auditing would be the cornerstones of the system.

Thirty years later, we may conclude that certification turned out to be an expensive concept, that market premiums are relatively low and often do not reach the farmers, and that labels are losing relevance as differentiators because of the dominance of labeled products. Unfortunately, consumers did not turn out to be the major drivers of change as originally expected. Third party auditing also turned out to be less reliable than hoped and a code of conduct was too rigid to stimulate continual improvements.

Given these unexpected outcomes related to our early ambitions, standard bodies are looking for innovations to overcome the shortcomings of past approaches. Moreover, many farmers and companies are already moving beyond certification towards more ambitious post-certification approaches. New technologies will stimulate these new approaches and will help us to define the business case for sustainability – whereby sustainability really supports the farmers – as the real driver of change.

Originally published on LinkedIn.