Why does intensification have to be combined with diversification, producing the same volume of cocoa on less land?

Why can deforestation not be stopped unless alternative options are offered to communities living in the forest belt?

Is the reputational damage of cocoa producing countries caused by Tony’s Chocolonely slave free marketing larger than the positive effect of the brand?

Let’s stop talking about cocoa farmers; they are just farmers with the capacity to serve different markets with a range of produce.

During my recent visit to Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire the above topics were discussed, among many others, during high-level meetings with the prime minister and ministers of Côte d'Ivoire, the Conseil du Café et Cacao, Ghana Cocoa Board, African Development Bank, the Swiss and Dutch embassies, with businesses and farmer organizations. Discussions were evaluated as being a wake up call. We together have to become more effective and smarter in combating sensational anti-slavery news while creating better futures for farmers.

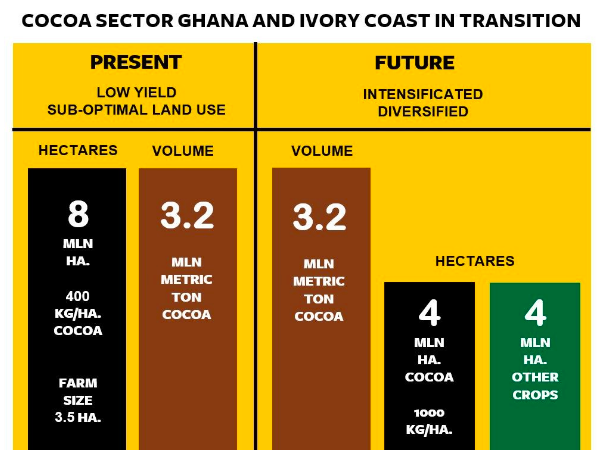

The economic dimension: same volume, less land

Some people question the continuation of the past decades’ strategy which has mainly focused on raising the productivity and quality of cocoa production in West Africa. In the end, their understanding is that higher volumes have led to lower prices for farmers. The promising higher market demand with high expectations of growing consumption in Asia turned out to be wishful thinking. Farmers seem to be back to square one.

However, deeper analysis shows that it would be irresponsible not to unlock the potential of doubling productivity from an average of 400 kg per ha to at least 1000 kg in a very competitive global market. In order to avoid higher volumes in the market, the same national volume could be produced on 50% of the land currently being used for cocoa production. More production on less land is a better strategy than just ignoring productivity. The area freed-up can then be used for alternative crops – like rubber or palm oil, or vegetables, fruits or potatoes – to serve local demands and that are compatible with the major environmental and social concerns which have been linked to an expansive cocoa production. Do not confuse volume of production and productivity was the clear conclusion.

Increased productivity enables the farmer to diversify and raise his or her income and the ability to de-risk price fluctuations.

An intensification and diversification scheme will minimize the area used for cocoa production, while increasing the productivity. It will also provide income gap fillers across production seasons to sustain farmers’ livelihoods and de-risk income sources.

The social dimension: Tony's Chocolonely, welcome to the real world

There is a vast library of reading materials available about social issues surrounding West Africa’s cocoa sector. They generally limit themselves to analysis and unfortunately don’t offer a scale of solutions.

During my visit to the region, our discussions were focused on the issue of child labour and slavery. The partners I engaged in various conversations were concerned about the unjustified negative reputation of the sector in Western consumer countries. The branding of Tony's Chocolonely as being on the way to slave free is for many a stumbling block.

Let’s take a close look at this. The successful Tony’s Chocolonely brand positions itself as ‘slave free’ and talks about 2.1 million cases of child labour and at least 30,000 cases of slavery in Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire. There are 2.3 million cocoa farmers in the region, so with 2.1 million cases of child labour we are talking about a typical characteristic that dominates the sector. Perceived child labour would be everywhere.

For a better understanding of the realities in the sector we have to make a distinction between child work and child labour.

Child work is the assistance children give their parents helping them on the farm, after school and during holiday times. As I did as the son of a Dutch tulip farmer, and I was happy with that. African parents are caring, they love their children. Like elsewhere in the world. Farmers want a better future for their children. So they do not exploit their children, but they need their helping hands. A poor economy comes with challenges.

Child labour is future destroying work that compromises a child’s development. Child labour is working all day instead of going to school. Hard, heavy and unsafe work beyond the capacity of a growing child. Honestly this is becoming a rare phenomenon in the region which has seen rapid growth in school participation numbers. Indeed, there are vulnerable groups, for example the children of migrants coming from surrounding countries who suffer from even more extreme poverty. These children do not attend schools during their temporary stay. Special attention for this group is crucial and urgent.

And more accurate insight into the status of child work and labour helps us to identify these specific cases and to develop tailor-made solutions. Bold statements with big figures do not reflect the structural labour situation of cocoa production in West Africa, unless it serves a marketing strategy. The attention on unbalanced news is growing but does not stimulate collective action.

And what about slavery? Clarity starts here with making the distinction between ‘slavery’ and ‘modern slavery’. In as much as these two terms could be closely related in many ways, the fact that recent reporting has qualified ‘slavery’ with the word ‘modern’ means a lot. Tony’s Chocolonely plays with the word’s semantics to drive a marketing agenda in its favour. ‘Slavery’ is the widely perceived knowledge of historic slavery going back centuries. The intercontinental slave trade was an extreme form of systemic deprivation of liberty, racism, exploitation and human rights violations. However, the Global Slavery Index refers to ‘modern slavery’. The widely held appreciation and general sentiments as well as sensitivity around the two are not the same. While historic slavery is still left without serious apologies from the West, new allegations are brought to the table by Western consumer brands in a confusing mix of terminology which suggest comparable situations.

The definition of modern slavery essentially refers to situations of exploitation that a person cannot refuse or leave because of threats, violence, coercion, deception, or abuse of power. The issue of what exact practice, be it deception, coercion or violence is unclear. Thus, most issues and the contexts have been bundled up together.

It is time for Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire to request a new evidence-based labour conditions study by independent institutions. This would take into account over two decades of industry, national systems and civil society investments through projects, programmes and actions to address child labour and responsible labour use in the sector. Be mindful – even one case of children’s rights abuse in the sector would be unacceptable and must be addressed.

The Global Slavery Index estimates 133,000 people to be in modern slavery in Ghana, and 137,000

in Côte d'Ivoire. That’s less than 0.4% of the population of both countries. Of course, each victim is one too many. However, fortunately, modern slavery is rare. And historic slavery – which is the picture in consumers’ minds – no longer occurs in the cocoa sector.

Another remarkable ‘fact’ in Tony’s incorrect information is the calculation of the average income of a cocoa farmer of ‘only 46 euro cent a day’. Research shows different later figures from 2016; for Ghana 2.89 USD per person per day and for Côte d'Ivoire 3.11 USD per day. Moreover, scientists are strongly in favour of calculating income per households instead of per person to get the right picture. Again, exaggeration in an already serious situation is not helpful. Only fact-based strategies work.

The ecological dimension: gaining the support of forest farming communities

Ecologically speaking, in terms of cocoa production, our main concern is deforestation. It is a known fact that from historical times to the present day, cocoa has been planted in areas which were once forests. There is also evidence that farmers have encroached on protected areas to clear forest and plant cocoa. Most often, timber exploitation comes before forest clearing for cocoa. Thus, farmers take advantage of the reduced residual stem numbers following legal or illegal logging to further open up the forest and plant cocoa. Over time, interventions have been put in place by different parties to address the issues of cocoa-driven deforestation. However, recent satellite imagery of the cocoa landscape shows that these interventions have resulted in minimal benefits in reducing deforestation and transforming monocultures to agroforestry which would restore the tree cover in the landscape.

Dark green activists are advocating for the removal of farming communities from the forest to restore high value conservation areas. This doesn’t seem very realistic. There is minimal political will and societal support for these kind of drastic measures and no direct alternatives for these people.

Local communities’ buy-in is the decisive success factor for a lasting change. Solidaridad is focusing on building the necessary local alliances and support. It is important to roll out various interventions, but the most critical aspect is to ensure that these interventions are implemented in synergy with one another. They should also take place consistently over long periods of time, alongside corresponding incentive systems for farmers. Solidaridad recommends the following interventions to halt and reserve cocoa-driven deforestation while creating new perspectives for forest communities:

- Cocoa intensification and rehabilitation

- Livelihood and cropping system diversification

- Youth-driven agribusiness

- Forest and land governance

- Improved forest landscape monitoring

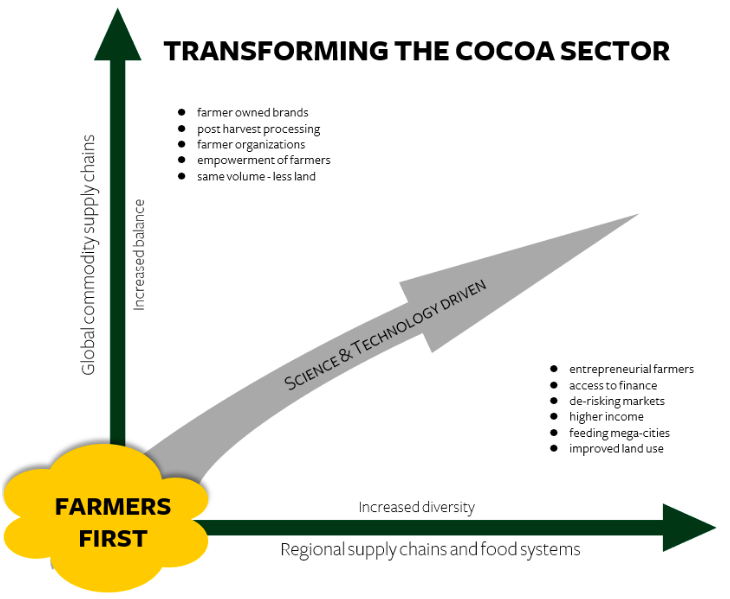

Local ownership first: turning the picture around

My main conclusion after intensive discussions with our stakeholders in the region was that Solidaridad is in the unique position to support local ownership of strategy and programming.

Our local team – the boots and brains on the ground – under local management and supervision can take the role to co-create a national framework for sustainable development of the cocoa sector. A lot of NGOs are just doing the talking or are claiming the work of others. Business interests are driving the agenda and governments are redefining their role. The kind invitation to present an action plan to governments in the region could be the entry point for creating this innovative process of rethinking strategies. Our farmer first principle gives a new perspective for addressing, in an ambitious and realistic way, a new programming based on local understanding of realities.

Identifying the underlying causes of sub-optimal performance is simpler than assessing the prevailing magnitude of each issue, let alone formulating and implementing solutions at scale.

———-

Tony’s Chocolonely: 100% slave-free chocolate

Tony’s Chocolonely is a rapidly growing chocolate brand which sells its products in five European markets. The ambitious, sustainable brand appeared in the Dutch consumer market in 2005 and has built up a market share of 19%, overtaking multinationals like Verkade, Mars and Nestle. Tony’s Chocolonely sources cocoa from a little over 5,000 farmers organized in six cooperatives in Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire.

———-

Cocoa industry best practice

The five game rules of the company can be seen as a best practice in the cocoa industry.

- First, the so called ‘Beantracker’ guarantees full traceability throughout the supply chain. This is no small achievement, given the complexities from farm to fork.

- The second rule is a higher price at farm level. Tony’s pays the official fair trade premium plus a living income premium. In Ghana this comes to 375 USD per tonne, and in Côte d'Ivoire 600 USD per tonne. This is substantial money for poor farmers and unprecedented in the market.

- Thirdly, the preferred trading partners are cooperatives. Tony’s supports the development of this type of cooperation among smallholder farmers.

- A long-term contract of at least five years is the fourth cornerstone of their trading practices.

- And the last rule is the focus on sharing best farming practices to improve the productivity in the cocoa industry.

In a recent study the Walk Free Foundation and Tulane University concluded: ‘there are no recent cases of slavery found in the partner cooperatives of Tony’s Chocolonely’. So far nothing wrong.

Controversial marketing strategy

Tony’s Chocolonely market profile is ‘slave free', with a prominent focus on the supposed number of ‘2,100,000 children working in Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire under ‘illegal circumstances’ and ‘at least 30,000 victims of modern slavery.’ Those adults and children are apparently ‘forced to grow cocoa without any payment’.

These messages are allegations without evidence and could be seen as fake news; far beyond reality. From our recent knowledge of the sector it is clear that the communicated numbers can not be true and earlier studies throwing out these numbers must be revisited. It is obvious that the concepts of child work, child labour, forced labour, slavery and modern slavery are being used interchangeably without clear definitions On the other hand, the picture of slavery in consumers’ minds, is that of the historical one. Hence the declaration of ‘slave-free’ chocolate practically paints a picture of the historical slavery rather than modern slavery. The sentiments attached to slavery do not reflect the reality of today.

For sure there are many issues to be addressed. But exaggeration will not unite people in finding common solutions. Unnecessary reputational damage will harm the sector and, more importantly, the farmers who desperately depend on cocoa. It is obvious that the company took advantage of a few occurrences of deviant behaviour to characterize the cocoa supply chain. Essentially, the fact that deviant behaviour can occur does not mean the deviant behaviour is a typical characteristic that dominates the sector. This is a rather cheap way to drive a marketing agenda, which

is unfair to other industry competitors who have invested in innovations to scale.

Child labour in the region is no longer systemic, but incidental. Child protection is a defined policy and, in Ghana, school attendance is already at a level of 94%. In Côte d'Ivoire is it also rapidly increasing from the current level of 64%. Poor economies are a challenging environment, but poor, misleading messages do not help.

Unbalanced supply chains

The real challenge for Tony’s Chocolonely is to create a more balanced supply chain. Transparency and a fair price are of great value. However, in essence, these are easy solutions because at the end of the day consumers will pay. The next battle will be for shareholders to pay a fair share of the added value generated in the supply chain and have a fair say in decision making. In the media, Tony’s director and majority shareholder Beltman dreamed about selling his company to one of the multinationals speculating about its value, and the huge profit to be made. Instead of earning a fortune, he could consider dividing the profits with the producers, giving them shares in the company.

A dream? No, this is already a reality. In 1996 Solidaridad created AgroFair, a successful banana trading company with 35% shareholding position for the banana farmers. As fair trade suppliers, the farmers get not only a fair trade premium but also a dividend based on their shares. Since 2008 their shares generated a capital transfer of 3 million euro to the farmers and the fair trade premium was 33 million dollar. An inspiring example for a chocolate company with a high ambition to combat poverty.

NR

Comments? Share them over on LinkedIn

Read more about Solidaridad's cocoa programme