Momentum for diversification

Tea is still the most consumed beverage in the world and India is one of the main consuming and exporting countries. Tea offers employment to over 1.2 million people. Through its forward and backwards linkages, another 10 million people derive their livelihood from tea.

Yet the tea sector is experiencing a sustainability crisis stemming from continuous low prices squeezing the tea producers. Moreover, both large and small farmers are facing the challenges of the high cost of production and low price realization. The starkly contrasting situations of profitable downstream actors and suffering upstream ones makes the supply chain unfair and unsustainable.

Oversupply is one of the primary reasons for price stagnancy. Moreover, the cost of production has been constantly increasing, which is not being compensated by the prices. Actually, the majority of tea bushes are more than 50 years old making it urgent to consider replanting or even smarter to explore alternatives. Indeed, the broadly shared conclusion is that it is time to define new revenue streams to supplement the low income from tea production.

Palm oil is showing the strongest potential

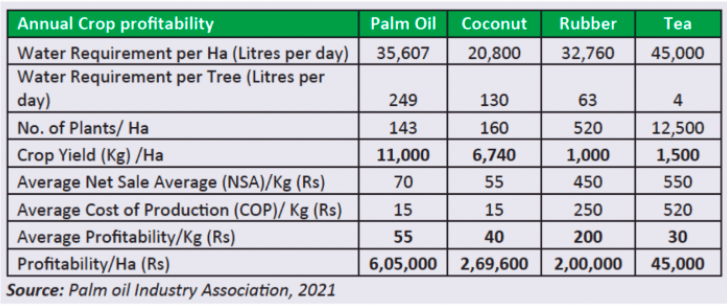

Diversification is seen as a key strategy for the next decades. The soil condition of tea garden areas is suitable for cultivation of large numbers of alternative crops. For example horticulture, floriculture and medicinal plants are new routes. The setting up of dairy farms to generate manure for organic production is another win-win strategy, also serving growing local demand for dairy products. However, the highest potential for moving out of poverty will for sure be palm oil.

Feasibility studies on the performance of oil palm in the traditional tea estates of Assam and West Bengal in India have proven the potential and underlined the need for a review of the land utilization policy by allowing alternative use of the land. Colonial laws from British times still guaranteed the dominance of tea, historically assuring the continual flow of tea for European demand. The recent announcement of the Indian government to intensify oil palm cultivation covering the immediate potential of 48,000 hectares shows that the traditional roles on global markets finally belong to the past. The upwards potential is even higher, mounting to 650,000 hectares by 2026. This theoretical potential has to be balanced with environmental concerns and a broader diversification.

Rejecting Western myths on palm oil

The recent decision of the Indian government to go for palm oil challenges the dominant anti-palm oil rhetoric in Europe. The Asian perspective understands better that simply linking palm oil to deforestation is wrong. Local knowledge is that the future of palm oil is sustainable palm oil, not boycotting this crucial crop for the development of their economies.

Serving the urgent need for affordable cooking oil for millions of poor consumers is a top priority. Suggesting that there is an alternative at scale for palm oil is a misleading message. Sustainability starts with the efficient use of the scarce resource of land. Palm oil is five times more efficient than vegetable oils from moderate climate zones.

Moreover, palm oil is a business opportunity for farmers. As long as the vast majority of Western brands refuse to pay for a living income for coffee, cocoa or tea farmers, palm oil provides the unique opportunity to survive as farming communities. Switching from tea to palm oil will strengthen the poorest layers of the Indian agriculture sector without any deforestation, just reusing the land under cultivation for a more profitable crop. Like many smart farmers have already done in Indonesia, Malaysia, Honduras or Colombia. If the indirect effect of taking out huge areas of production for tea would reduce the oversupply of tea leading to higher prices both farmer groups will benefit.

Beyond certification

Analyzing the benefits of sustainability certification programmes in the tea sector Asian analysts see an imbalance in positive effects. While certification does provide reputational benefits to the tea packers and brand owners, there is no strong business case for the tea producers to get themselves certified through an expensive third-party auditing process. Sold certified volumes remain relatively low and by consequence price premiums are not real change makers. In spite of all good intentions. Moreover, tea has gotten the least amount of global climate funding compared to comparable commodities. Also, NGO funding for sustainable transition is relatively low compared with other eye-catching commodities.

Interesting is to see the differences in market dynamics. In the coffee and cocoa markets a high-quality segment has generated higher prices for the best performing farmers who are able to serve these demanding markets. The Nespresso cup revolution has upgraded the taste and the experience of coffee, making consumers more aware of differences in coffee qualities; and they are ready to pay for the better ones. Also in the chocolate segment branded quality pays.

For sure the brands benefit the most from the additional margins, but there is some trickle-down effect to producers too.

In the tea market, just the opposite has happened. Tea is still a beverage ingrained in many cultures and is a part of the daily ritual of many people, all over the world. However, the tea bag revolution has provoked a dramatic downgrading of taste among consumers, moving away from loose tea. In general, the content of tea bags consist of the low-quality tea grades and offers no tea leaves, but just dust of tea.

Moreover, on European markets, a litre of regular black tea costs only 30 euro cents, while a litre of Coca Cola costs 180 euro cents. Consumers pay a low price for a healthy tea and a high price for a high-sugar product lacking nutritional value. The difference is made by the power of trendy branding misleading consumers about the quality of products.

In fact, black and green teas are losing market share. On the supermarket shelves, herbal teas have become a hype, generating higher margins in the end consumer markets.

Recently Unilever, once the sustainability pioneer, sold its tea business for 4.5 billion dollars to go for processed food, health, beauty & care; all categories generating higher profits. Leaving the tea producers behind in the hands of an opportunistic private equity investor. Unilever’s sustainability rhetoric on tea became a serious disappointment for farmers, resulting in a high score on the more harm than good ratio for the failing change maker.

One thing is clear. The prosperity of the tea sector relies on viable farmers and the business-as-usual scenario is not sustainable for the workers, farmers or the brands.

Adding a valuable crop to the portfolio of Indian tea farmers will not only save foreign exchange outflow of the country, provide significantly better returns to the producers, but also create the demand-supply balance for tea so essential to push the quality and price.

The continually increasing demand for palm oil combined with the zero-deforestation commitments of Asian governments creates an opportunity for sustainable agriculture. Combined efforts and pre-competitive cooperation in the Asian region with respect for all interests will generate the best results. Adding anti-palm oil campaigns to the already existing geopolitical tensions in the world is counterproductive.

Read the full article:

About the author

Nico Roozen is the former Executive Director of Solidaridad Network and the current Honorary President to the International Supervisory Board. Follow on LinkedIn for more articles from Nico Roozen